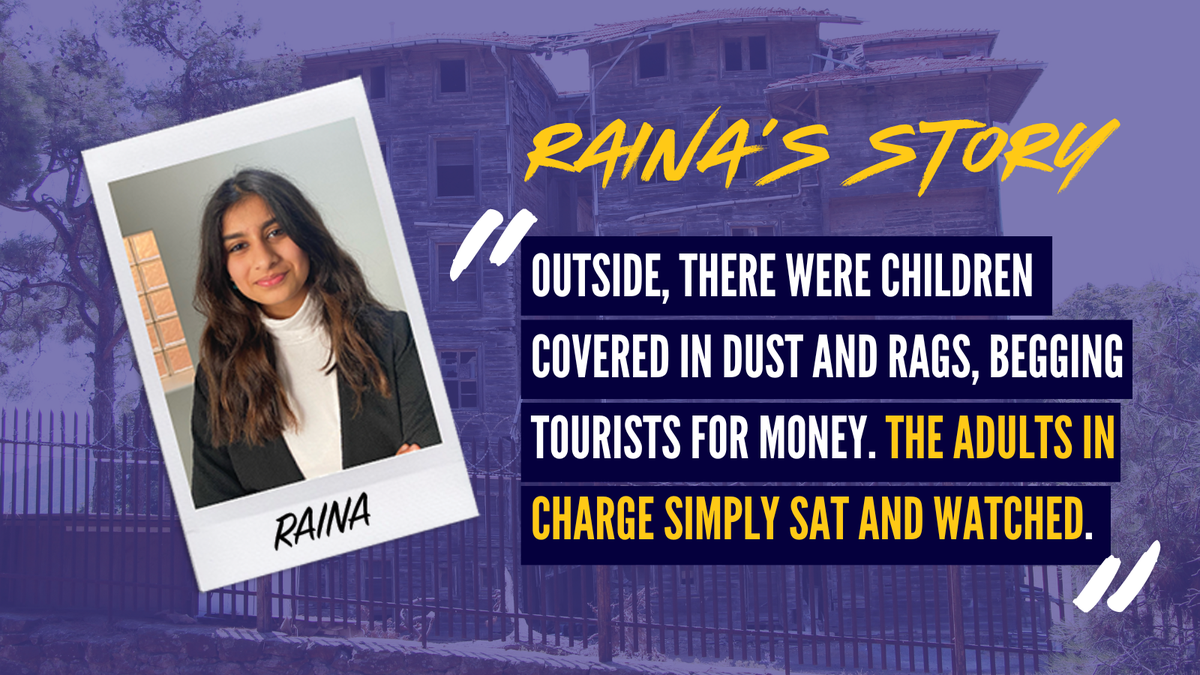

“One day we passed a little orphanage with mud and brick walls. Outside, there were children covered in dust and rags, begging tourists for money. The adults in charge simply sat and watched.”

In 2017, my family and I headed to India. I was excited to immerse myself in rich Indian culture, explore the enchanting city of Agra, and go road-tripping from the Taj Mahal to ancient Mughal forts. At the age of 12, it was a trip that opened my eyes, in so many ways. The children I saw in India inspired my work today as a sixth-form student campaigning against orphanage tourism and child exploitation.

AN EYE-OPENING EXPERIENCE

During the trip, we visited towns renowned for their incredible temples. Although their beauty took my breath away, I also noticed many homeless children around. I remember one of the girls, perhaps the same age as me at the time, covered in dust and wearing scraps for clothes. She followed my parents, begging them for money, but wouldn’t accept anything to eat or drink.

We visited Kerala, celebrated for its natural beauty and luscious tea plantations. Here too, I saw so many homeless children. Around the tourist sites, there were children begging or selling trinkets. One day we passed a little orphanage with mud and brick walls. Outside, there were children covered in dust and rags, begging tourists for money. The adults in charge simply sat and watched. Tourists stopped to interact with the children, taking photos with them and giving them money.

I remember one day, as we took a taxi tour with a driver in Kerala, we stopped at an intersection and a young boy came up to our open car window to ask for money. His arm was cut off just below the elbow and was clearly infected. Our local driver quickly rolled up the windows, telling us to not give him any money. He explained that donating would only support the boy’s ‘boss’ and make the boy more open to exploitation.

REFLECTING ON MY EXPERIENCE

Years later, as a sixth-form student, I worked with the UN World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) for a Model UN conference on the topic of orphanages. I soon discovered how foreign support unwittingly helps maintain ill-equipped institutions, and how orphanage tourism encourages child exploitation and trafficking. I also realised I may have witnessed these things in action in India. The orphanage I saw in Kerala was ill-equipped to care for children, with a clear lack of resources.

I was determined to find out more about organisations that fight these institutions, but I was alarmed by the lack of ways for me to help. When I talked to my friends, none of them were aware of the negative impacts of the orphanage industry. I admire Lumos’ #HelpingNotHelping campaign for working towards a fix and spreading awareness.

Fuelled by continued support from well-intentioned tourists, the cycle of children living in these inadequate living conditions will only continue. Hopefully, there will be better government legislation, more preventative measures and increased awareness of the problem in the future.